Lifespan, David Sinclair

It’s a good book …

If you enjoy thinking about possible futures and indulging in science fiction you may have come across the idea that, one day, science will help us venture beyond our biological barriers and extend our lifespans indefinitely. While David Sinclair doesn’t seem to suggest this will happen just yet (contrary to some more outspoken residents of Silicon Valley), his book Lifespan, Why we Age and Why We Don’t Have To, elegantly introduces the reader to his information theory of aging and what we may do to be able to slow it down before eventually getting rid of this disease altogether. And yes, it is Dr. Sinclair’s view that aging is a disease and should be treated as such, which I’ll get into below. He also covers a host of ethical and societal considerations throughout the book whilst summarizing a lot of the research he has conducted over the past years. Personally, I read the book adamantly and it has inspired me to read more about the field of aging keep up to date with the research in the field.

Aging is a disease

Of course, I am highly biased as I’ve read the book and am quite enthusiastic about a lot of what our Australian professor writes about, but doesn’t this idea that aging should be considered a disease -in itself- just seem so obvious? As we age, our entire body slowly and painfully grinds to a halt. Surely this is a disease. But so why don’t we consider it as such? I should note that at this stage you can do us both a favor and throw the “it’s natural, it’s not a disease” blabla back to wherever this astoundingly ridiculous concept comes from. The day you are, god forbid, diagnosed with any kind of illness I should hope your doctor doesn’t respond to you by saying, just accept it bro, it’s natural. Diseases are “natural”, to take the definition literally: they occur in nature, and so does aging. Unfortunately for us, it seems Nature doesn’t really care if we live or die, so I’d rather go the non-natural way and trust medicine/research based on solid science. However, some scientist and doctors don’t seem to think it’s such a good idea either to consider aging a disease. I won’t go into the semantic implications of calling aging a disease covered in the link, but it seems the disagreement is rather superficial. It’s also worth mentioning, that these considerations are inconsequential compared to the increase in funding calling aging a disease could bring to the field and all the potential breakthroughs that might arise thereafter. If, as Sinclair writes, there is an exponential increase in other diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular illness, diabetes, dementia, stroke etc.. as each year passes after the age of 20, I’ll call aging whatever you want just so that it receives more funding. Trying to address the root cause of all these problems rather than investing all our efforts into treating the individual diseases listed seems to be a more efficient use of time and money.

How does it work?

I won’t pretend I’ve truly digested all the content in the book regarding the mechanisms at play but I’ll try to give a TL;DR version nonetheless (in terms I can understand without having to do some good old-fashioned copying). And I should note that perhaps it’s because I’m a little more math oriented but I find the Information Theory aspects of this book’s explanation of aging particularly clear and fascinating, so that may transpire in this account.

According to the author, aging is quite simply a loss of epigenetic information over time. (The epigenome is essentially the whole machinery around your DNA which allows different genes to be switched on or off and controls levels of expression). The analogy from the book I find most poignant is that of the DVD player. DNA is discrete, digital information that is stored within each of our cells, and this is what we can call the DVD. Then comes the epigenome which reads and makes sense of the digital information, it is the DVD player, and it stores its information in an analog format. Rather, it converts the digital data to analog as it reads genes which are stored digitally but regulates gene expression levels which are continuous variables. This is precisely where aging occurs, accumulation of epigenetic noise means the information content of the analog data doesn’t hold over time, our reader can’t seem to make sure the right genes are expressed at the right level. Of course, scratches on the DVD (or small breaks and alteration in DNA) represent damage to the digital data, but the problem is more that these scratches can impair the whole analog reading mechanism even if they occur at places we wouldn’t deem important. Think of a scratch during the opening credits of a movie making the whole thing not work. Of course, there are many more intricacies to this theory I won’t delve into, and regardless of whether it is actually true or not (experimental results on yeast and mice suggest it is), isn’t it elegant? It remains a philosophical debate whether the simplicity and elegance of a scientific theory hold any predictive powers as to its veracity, but setting this aside I think it’s possible to simply admire an elegant theory for its own sake. Of course, Sinclair et. al would perhaps rather go into what exactly this information theory of aging means to those who want to solve it.

Can we slow and reverse it?

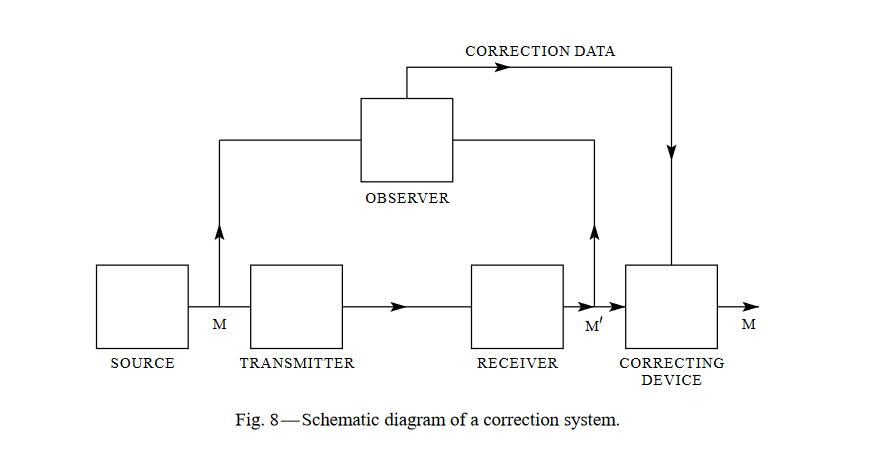

Now that we have a very basic understanding of the process in itself, the question naturally arises as to what the best course of action is to try and preserve as much epigenetic information as we can. Drawing once again from Shannon’s A Mathematical Theory of Communication paper, the book suggests that we should find the biological equivalents to the components of the transmission system presented in the paper designed to recover lost information.

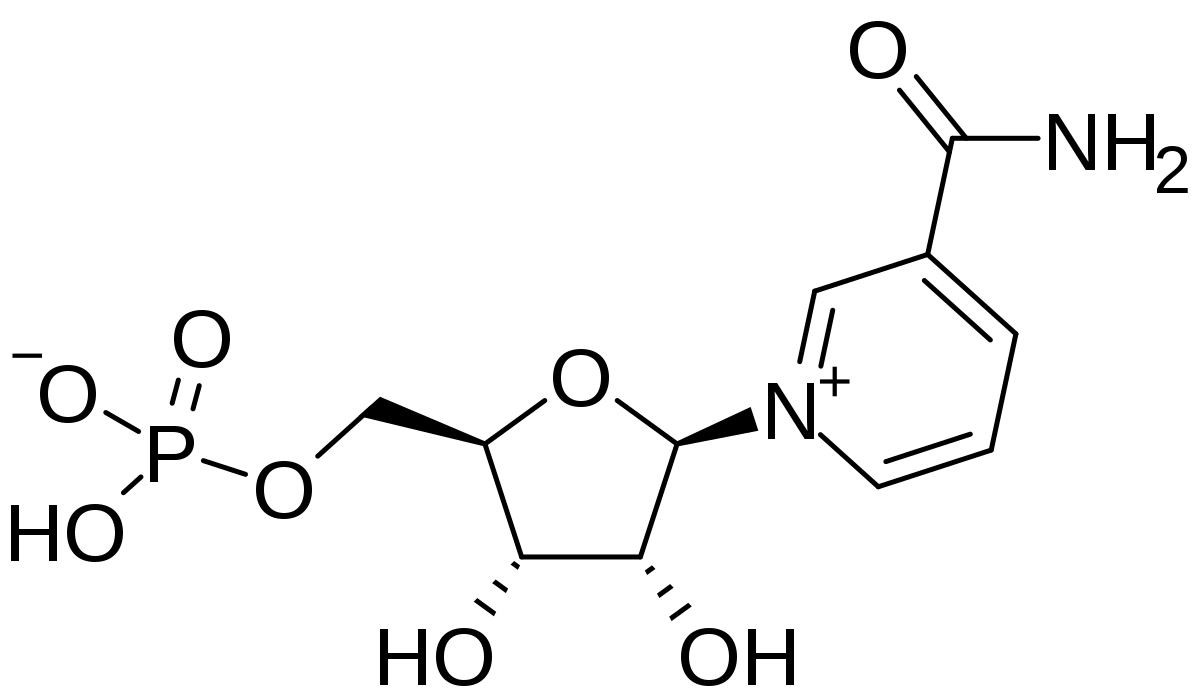

Creating a similar system in our own bodies could be a solution to this loss of epigenetic information. (Side note: cf. the paper but it seems ergodicity is everywhere and not just this blog!) Although, unfortunately, theoretical considerations around actual information theory such as, channel and noise entropy or transmission capacity of the biological channels considered here, remain fairly shallow in the book, Sinclair goes deep into the biology of the possible “correcting device”. There seems to be a set of genes that are good potential candidates for the correcting device that have been used to restore cellular identity and Sinclair’s lab is actively working on making this an implementable reality for humans. The possibilities for delivering these genes and activating them are numerous but the important thing is that you could switch them on and off and control the process of cellular rejuvenescence quite precisely. It remains a mystery and is therefore an area of active research as to who might be the observer and how they might be obtaining source and receiver information before supplyng correction data. Of course, aside from actually reversing aging through these correcting genes there are other possible solutions to the problem of aging. The book highlights three, what are referred to as, “longevity pathways”. These pathways engage survival mechanisms in the body and activating them has been shown to extend healthy lifespans of mice and other species in the lab. The interesting thing for us readers and possible consumers, is that one can ingest molecules such as NMN that are precursors to NAD.

Check the link or the book for more detailed explanations on exactly how this works and why NAD is such an important molecule for our bodies, but the cool thing is, it’s a fairly straightforward first step in the battle against aging. This is probably the right time to note that, these and other methods that are currently being worked out will likely only supplement an already healthy lifestyle. If you’re chronically overweight, never do sports and frequently overeat, or smoke, or do a host of other things that are terrible for our bodies, that’s probably where you should start in the battle against aging.

Just give me the pills and what I should do on a daily basis

Do you want to live forever? Then buy these pills which you can find at the following link https://sebastianpartarrieu_pills_to_make_you_sexy_and_live_forever, of course completely unafilliated to the present blog. A little more seriously, Sinclair shares in the book what he takes on a daily basis and some habits that can help live a longer, healthier, life. As he mentions, this has not been subject to rigorous long-term clinical trials and is therefore definitely not medical advice. It’s more personal experimentation than solid science for the moment, but here goes:

- 1 gram of NMN every morning with 1 gram of reseveratrol and 1 gram of metformin

- Daily dose of vitamins D, \(K_2\) and 83 mg of aspirin

- Keeping carbs low

- Skiping one meal a day

- Blood analysis every couple of months to analyze dozens of biomarkers

- Walking/sports as a daily habit with some temperature stress thrown in there

- No smoking, no microwaved plastics, no excessive UV exposure, X-rays or CT scans

- Cool side for sleeping (check out an upcoming blog plost on Matthew Walker’s Why We Sleep to understand why this is important) and during the day

- Body weight kept in optimal range for healthspan

To be honest, a lot of these are nothing more than common sense or at least have been generally accepted for years now. Personally, I manage to do everything on the list fairly easily apart from the pills and vitamin supplements as well as the frequent blood analysis. Being just 21 I figure I can focus on building healthy durable habits in my 20s and start seriously looking into supplements and blood analysis in a decade or so, even though I think monitoring one’s health proactively with all the technologies available to us now is a must. Hopefully, results from all the clinical trials being conducted on whether these substances are beneficial for extending the healthspan of humans will have yielded results by the time I need to start taking them.

Somewhat related - proactive healthcare

This is a topic I’d also like to delve further into in a future blog post but as the book touches upon this I might as well give my two cents on the matter. Proactive healthcare is the simple idea that we should be, yes, proactive rather than reactive when it comes to our health. It is much easier to take the correct steps to ensure disease doesn’t occur in the first place rather than have to deal with it when it comes. Achieving proactive healthcare requires some effort from the part of the individual, no doubt. Following some of the more basic steps we discussed above is a good start. Even better is putting in place monitoring systems that alert us before any potential problems arise in our bodies. This works by first tracking relevant data produced by our bodies before making sense of it and gaining an overall sense of our health across a given period of time. The possible data is plentiful and includes biomarkers in our blood as has been mentioned above but also simply relevant signals such as heart rate which can be tracked with a smart watch or any other kind of wearable smart device boasting the appropriate sensors. Doesn’t it just seem outrageous that concepts of predictive maintenance and prognostics health management are readily applied in industrial settings but we globally fail to do so with our own bodies? Of course, a spinning turbine has less moving parts and is therefore quite a lot easier to diagnose than a human being, yet, the fundamental idea that treating problems only after they arise is terribly illogical and inefficient bridges the gap between factories and bodies. Ideally, in the near future we will all have access to personalized AI health assistants that use all the data extracted from our bodies to give us daily recommendations and feedback on our current health status. All of this is pretty nifty if you ask me, I’ll be sure to follow the developments of personalized and proactive healthcare in the years to come. Finally, solving aging is perhaps the ultimate proactive stance when it comes to healthcare, as aging is the risk factor of most deadly diseases.

Clinical trials to follow in the near future & miscellaneous links

Here are a few links to clinical trials on humans to follow over the next few months and years that should help in evaluating whether the results presented in the book on yeast and mice hold for humans as well:

- To Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of NMN as an Anti-ageing Supplement in Middle Aged and Older (40-65 Years) Adults

- Metformin in Longevity Study (MILES). (MILES)

I seem to have found as many links explaining why designing these clinical trials is hard:

- Clinical Trials Targeting Aging and Age-Related Multimorbidity

- Strategies and Challenges in Clinical Trials Targeting Human Aging

(EDIT, thanks Phil!): some more links for interesting podcasts and surrounding information

- Peter Attia’s podcast, the drive, round #1

- Peter Attia’s podcast, the drive, round #2

- There are plenty of study in mice, some of which are regrouped under the Interventions Testing Program, sponsored by the National Institute on Aging

Conclusion

I hope you managed to get through this without a yawn and I sincerely recommend that you read this book. I not only learnt a lot by reading it but it has also shifted my perspective on something I thought was the realm of science fiction. Scientists like David Sinclair are truly a source of inspiration as they work tirelessly in the face of these monumental questions to bring knowledge forward, one step at a time. I look forward to observing how these theories grow over time.